Art Production Beyond the Art Market | He is NOT his Studio: Looking at Greg Sholette | Whitehot Magazine | art21: Inside the Artists Studio | art21: 5 Questions for Contemporary Practice | Jeffery Skoller: “Do It Yourself Art Action Kit!”

Leah Oates In Conversation with Greg Sholette

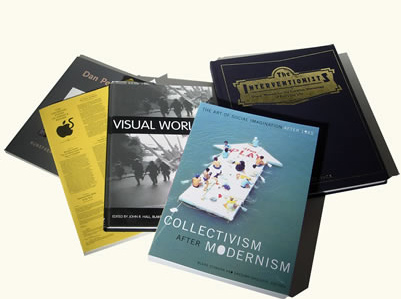

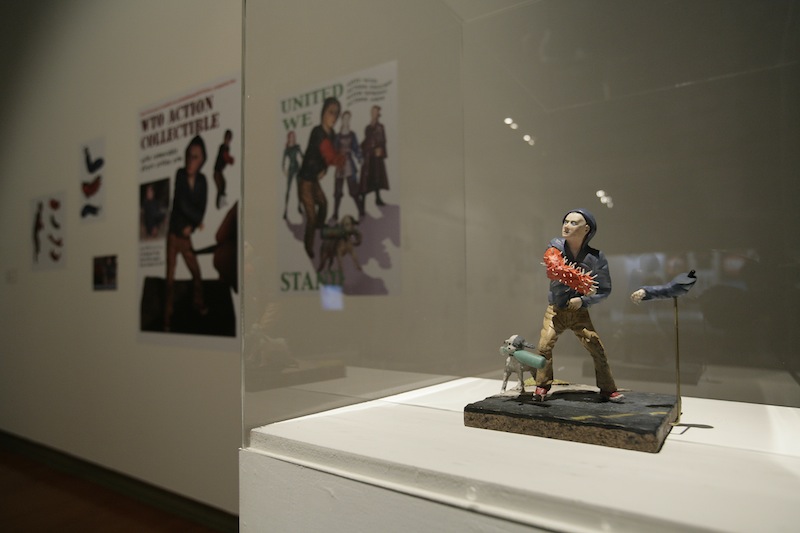

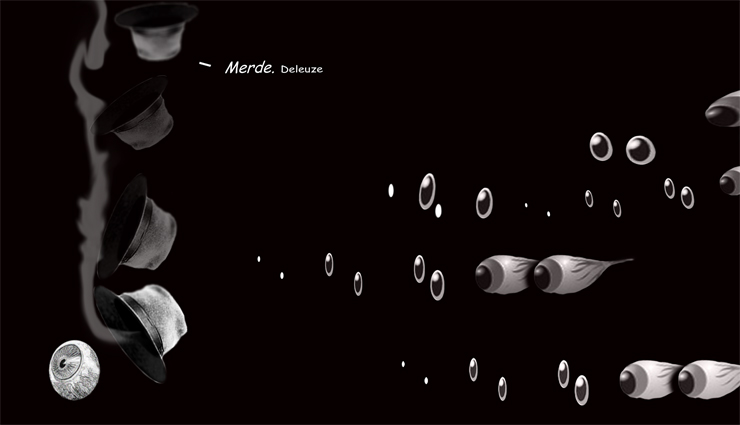

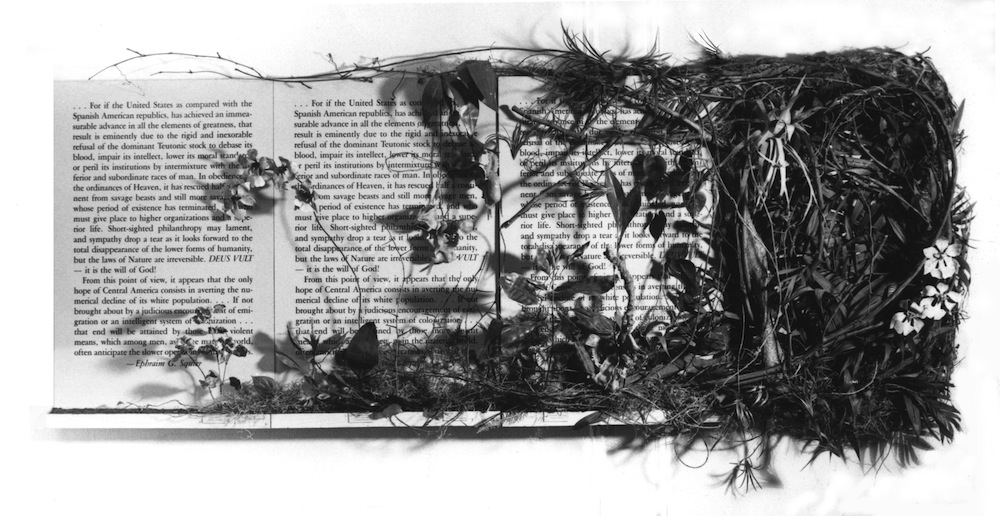

Greg Sholette, WTO Action Collectible Poster, 2013. Image courtesy of the artist.

Leah Oates: How did you become an artist and what is your family background?

Greg Sholette: To be honest, growing up outside Philadelphia watching Jacques Cousteau specials on television, my real childhood ambition was to become a marine biologist not an artist. You know, slip on a wetsuit, jump in a submersible, discover new types of sharks and crustaceans.

LO: And?

GS: All that was before my unhappy encounter with higher mathematics. We didn’t get along. Science was out. But my parents were. Though neither professionals nor academics (my dad sold automobile insurance for a living) I was encouraged to explore my obsession with drawing and making things out of cardboard to play with. Around age six they managed to set aside some money to send me to weekly art classes with a local watercolorist named Jeanne Doan Burford (who in fact just turned ninety).

I think its worth noting, Leah that I really don’t think before starting these lessons I was consciously making “art.” I mean drawing and so forth seemed more like a half-magical, half-megalomaniacal ritual or tool with which to manage, or escape the big, sometimes intimidating world of adults. Jeanne began to channel this intensity, focusing it with such classical exercises as collage, illustration, color mixing and the like. She effectively opened-up to me the possibility of my becoming an “artist,” something that my family background would have probably foreclosed as a serious option.

LO: Why do you say that?

GS: Because so much depends on seeing oneself succeed in a particular role don’t you think Leah, and there were simply no role models to follow. None within reach so to speak.

LO: But this was also what, the mid-1960s, there must have been other influences on you as well?

GS: Yes, and as clichéd as it sounds radical change was filling the air it seemed in those days. Nor was it lost on me. In 1970 I was caught stuffing student lockers at my Junior High school with an anonymous “underground” newspaper that my friends and I printed on a mimeograph machine, then state of the art reproduction technology. Bluish-green and terribly naive, the cover showed Mickey Mouse raising a clenched fist to decry the war in Vietnam, imperialist “Amerika,” and police brutality in nearby Philadelphia. I believe we also reviewed LPs by Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin.

LO: How did other students respond to this?

GS: I don’t recall any of our twelve to thirteen year old peers showing much interest in our paper, our politics, or the music we recommended. We on the other hand smoked pot, listened to protest rock, and worried about being drafted some five or six years down the road. I also can’t recall being invited to many parties.

LO: When did you actually realize you were going to be an “artist?”

GS: Not until about 1976 I think when I attended Bucks County Community College in Pennsylvania. There I met the artist Charlotte Schatz who was a brilliant teacher. She pretty much figured me out. She helped me get into The Cooper Union and once in New York my previous political leanings found an ally and mentor in professor Hans Haacke. But I also took some memorable classes with Louise Bourgeois, filmmaker Robert Breer, and art historian Dore Ashton.

LO: And after that?

GS: Well, after graduating in 1979 I became involved with the artists’ collective called PAD/D or Political Art Documentation/Distribution, which was co-organized with Lucy R. Lippard among others. About a decade later I co-founded the group REPOhistory with another gang of artists, educators and activists including Jim Costanzo (AKA Aaron Burr Society today), Tom Klem, Lisa Maya Knauer, Todd Ayoung, Lisa Prown, and Neill Bogan and among others.

LO: What does REPOhistory mean and what did you do?

GS: The name is a spin on the 1984 indy film Repo Man with Harry Dean Stanton, but our objective was to “repossess” lost or forgotten or suppressed histories of working people, women, minorities, radicals and then mark these in public spaces around New York City.

In 1992 we managed to get City permission (under Mayor David Dinkins) to install dozens of temporary, metal street signs around lower Manhattan revealing such things as the location of the first slave market on Wall Street, the shape of the pre-Columbian island coast line, Nelson Mandela’s historic visit to New York just two years earlier, and the offices of a famous 19th century abortionist named Madame Restell—once located where the Twin Towers also once stood. One side of each sign had an image. The other told the story.

LO: So you collaborated making art projects for quite a few years?

GS: Yes, but I continued to make my own work all along as well: wall pieces, dioramas, photo-based bas-reliefs.

LO: But how do these public, collective practices you’re your own art making overlap and inform each other?

GS: In retrospect I think my individual art making has functioned as a sort of refuge for experimentation that in turn feeds back into my more public practices, writings, teaching and so forth. For example REPOhistory was founded in 1989 with a sizable group of other people. However, my interest in exploring alternative ways to represent history had already found expression earlier that year in a nine-foot wide panoramic-collage entitled “Massacre of Innocence” about the death of children in historical battle zones. One year before that I produced a three-part photo-relief piece entitled “Men Making History/Making War:1954” about the politics of the McCarthy era. More of this work can be found on the back pages here.

LO: And this cross-pollination continues today?

GS: Sure, something similar is happening today, for example with my book “Dark Matter” whose themes about history, archives, and resistance reappear in my graphic novel “Double City” that is still in progress. I supposed this is why I prefer to describe what I do as an expanded art practice rather than calling it post-studio, or relational aesthetic, or even social practice art. Besides, as you know I like to make “things.”

Installation view of assorted Greg Sholette collectibles, 2013. Image courtesy of the artist.

LO: But when did you become a teacher?

GS: Short version is that during the mid-1980s I also tried to run a business. It was a prop and model-making shop located in the Gowanus area. The techniques I still use in some of my art stem from this venture, which, shortly after the financial crash of 1987 collapsed along with the local advertising industry. I decided to get my MFA. Heading west I attended the University of California in San Diego where, between 1992 and 1995, I worked primarily with French new wave filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin. No, I wasn’t making films (though I taught film theory), I was instead creating installations and sculpture influenced by cinema. After that I returned to New York as a critical theory fellow in the Whitney Independent Studies Program (ISP) where Benjamin Buchloh, Mary Kelly, and Ron Clark encouraged me to write about the kind of collective, political art of PAD/D and REPOhistory. It was excellent advice. But even with all this education and experience finding a teaching position took a long time to land. Its even harder today.

LO: Do you think the art world has gotten out of hand in terms of money and class elitism? Would it be better to go back to the good ol days of Max’s Kansas City and Warhol’s Factory?

GS: Those particular good ol’ days were somewhat before my time Leah, though I did arrive here as the East Village scene unfolded in the 1980s. Young artists showed their work in galleries like Nature Morte and Fun Gallery and also at various clubs including the Palladium, Danceteria, and Pyramid. Some even sought to reenact aspects of a 1960s SoHo they had only read about in magazines including Warhol’s Factory. In general East Village art was a compilation of campy gestures, or perhaps campiness to the second power, and its ironic self-consciousness dovetailed neatly with dominant versions of post-modernist theory.

LO: Where did you fit into this “scene” then?

GS: Yeah, well my outlook, as well as that of my friends and collaborators, was pretty skeptical. PAD/D for instance produced a critical parody of the East Village art scene in 1984. We claimed to open up four “new” galleries showing anti-gentrification art. In reality these exhibition spaces were just boarded up buildings on street corners east of Second Avenue. We named them “Discount Salon,” “Another Gallery,” and the “Guggenheim Downtown.” For several weeks that summer a group of about eight wheat-pasted posters denouncing real-estate speculators and spray-painted stencils calling on our peers to fight the displacement of low-income residents.

LO: Artists fighting gentrification? Did it work, did you reach your audience with the message?

GS: Yes, and no. But one way or the other our ersatz art venues and the actual galleries they satirized were soon enough replaced by trendy restaurants and boutiques.

LO: So things have really changed for the worse?

GS: Also yes and no. I mean maybe the feeling today that the art world has been swallowed by hedge fund operators, global real estate tycoons, and finance capital is not entirely new, no, but you could also say it is really like the 1980s art scene turned up full volume.

LO: That seems pretty bleak, no?

GS: Thankfully there is still push-back by artists and their allies. I am thinking of Groups like Temporary Services, Aaron Burr Society, Chto Delat, and Pussy Riot and many others who continue to do the kind of resistance PAD/D and REPOhistory were engaged in today, just as PAD/D and REPOhistory were continuing to do the work of Art Workers’ Coalition, Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, and Angry Arts and other groups that came before them.

LO: What about your own work? You might best be described as a conceptual artist and a political activist, writer, curator and educator, yes?

GS: Conceptual Art? Right because of my association with Haacke, Gorin, Lippard and the ISP of course this aligns me with this legacy. I guess that is true in a way.

LO: Correct, though?

GS: It’s an honor to have my art connected to theirs. Then again, labels are hard to make peace with (as much as they are impossible to live without). So yes, while I do try to maintain a theoretically informed practice at the same time my work does not look like “conceptual art.” In fact it often seems just the opposite: hand made, figurative, with low-brow, pop-cultural references. Sometimes my art even comes off as conspicuously “rearguard.” I mean, over the years my projects have made use of an odd assortment of things such as artificial plants, diorama techniques, comic book imagery, miniature tableau, and sculpted action figures in order to present narratives about history, class, and political injustice.

LO: So what is your working process like?

GS: Hard to describe, but I just finished David Joselit’s recent book “After Art,” and thought for a while I had the answer. Joselit starts off discussing the far too many images that are constantly coming at us from the Internet, advertising, cinema, TV, etc… And then he counter-intuitively argues that “art” is not getting lost in this image-blizzard. Instead it has become a powerful generator of what he calls format. What is format? He explains that if traditional artistic mediums lead to object making, then format establishes patterns that create links and connections across images and long threads of content. The format therefore, is how an artist re-uses images, or ideas in order to produce a work. One of his favorite examples is Pierre Huyghe whose art always changes form, but there is a range of ideas lurking behind each piece. So After Art is when artists stop making discrete “works” and instead reiterate and comment on existing materials, sort of like recycling with a mission.

LO: I can see a certain connection to what you do Greg.

GS: Me too. But then when I finished After Art and really thought about it I realized that if Joselit’s concept is correct, then my work suffers from format failure! I mean he subordinates mediums, materials and content to his morphing paradigm. But I still retain a relationship with all three in my “expanded” practice. When I make art, or when I write a text for that matter, I find that I am assailed by the specific concrete nature of form and content.

LO: Please Explain.

GS: Lets say I am trying to write about the concept of the archive. Despite every attempt to discuss it conceptually, I know sooner or later that I will be forced to dip down into the archive’s specificity: its sprawling mass of missing practices, lost details, and dog-eared documents. Its as if some archive-agency commanded attention from below. And this dusty dark matter force tears up holes in smooth surfaces and turns abstraction pathological.

LO: A conceptualist!

GS: Ok, why not. Because what has shaped my art and its working process is less some profound inner drive to become an “artist” (although I admit I am as attached to that romantic idea as anyone) and is much more like the result of a string of fortunate encounters involving certain individuals and groups, certain institutions and historical moments, even certain objects and materials. As much as I would like to claim I am in full command of this process it’s a collaboration of sorts, a collaboration with the past –thus my interest in archives and history– as much as it is with the future expectations of a more egalitarian society. So that when all is said and done “art” is for me at least the way we think thought in material, plastic terms, but also reciprocally, it is how certain events, ideas, hopes and encounters become thinkable to us. And it’s a process that sort of bypasses our best attempts at exercising total authority or control over it.

LO: What are your upcoming projects?

GS: I am currently working on a new iteration of Imaginary Archive (http://www.gregorysholette.com/?page_id=587) for Kiev Ukraine this Spring, which, given the situation there should prove pretty compelling. I am also continuing to add chapters to my graphic novel Double City, and I am especially looking forward to the solo exhibition of new work I am preparing for Station Independent Projects in the Fall.

LO: What advice would you give an artist who has just arrived in NYC and who is not sure where to begin?

GS: Do your research. Seek out like-minded people. Map out the terrain. Stay tough.

I Am Not My Office: Gregory Sholette Interviewed by Karen van den Berg for Art Production Beyond the Art Market?

Karen van den Berg: Greg, you have been writing about activist art,

collectivism, and the impact of the invisible mass for the art world for

many years, and your writings are quite well known within the global

discourse about art in public space and so-called socially engaged art.

What I found interesting is that you do not act in the role of artist in your

writings, meaning you avoid the presentation of your own work in your

writing. I would therefore like to know how you would describe your own

working practice as an artist. How would you explain your self-conception

as an artist, and how is it related to your writing?

Gregory Sholette: To understand one’s dual position as both a politicized

individual/thinker and also as an artist—or perhaps what Pier

Paolo Pasolini termed a “citizen poet”—demands today that one remain

ill at ease when inhabiting either role, I think; even if that means playing

oneself off against oneself. Or maybe the right tag here is actually

something like a citizen poet sans citizenship or state? Anyway, we—that

is to say, us faithless intellectuals, artists, curators, and administrators,

myself included—we live in a moment of uncertainty and divided loyalties,

and it would of course be easier to forget the convoluted nature of our predicament

if only “art” was an easy thing to do without generating contradictions. Don’t you agree, Karen?

KvdB: This is a very poetic self-description—so how could I not

agree? I like the idea of a citizen poet sans citizenship. But could you

still be a little bit more explicit? What does your everyday working

practice look like? Do you produce works without a specific event or

situation? Do you work on your own most of the time? Tell me how

I can imagine the job of a citizen poet sans citizenship.

GS: Depending on priorities, I divide my days between computer time

and studio work. Some of this is work promised for an exhibition or publication,

some involves new projects I hope to produce at some point.

At the moment, I am, among other things, finishing up an essay for The

Blackwell Companion to Public Art; doing research for a text on the idea

of color and also for an art project about the militant, ultra-Left organization

Madame Binh Graphics Collective (active in New York City in

the 1980s); working with UK theorist Kim Charnley on a book of my

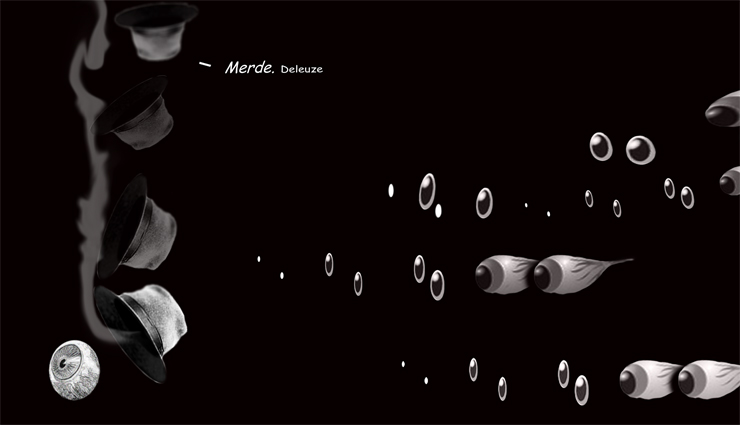

selected essays; and also developing the next chapter of Double City, a

graphic novel whose first chapter ran in the June 2013 issue of Frieze,

with the second installment appearing in Shifter 21 in October 2013.

(Double City is a science fiction narrative with a plot that seeks to address

issues raised by my book Dark Matter [2010], with subsequent chapters

hosting various illustrators and appearing in different publications as the

story unfolds.) And, to be perfectly honest, I feel that work is going on all

the time, even in my sleep sometimes because I often wake up trying to

solve issues related to ongoing projects. So much for the romance of the

citizen poet! But let me try out another label with you: let’s use “mongrel

researcher.” We could use it as a tag for artists involved in different registers

of practice, including traditional studio art but also collaborative

projects and online digital projects, as well as research, writing, lecturing,

and teaching that seeks to expand and reflect on the social conditions of

artistic production itself. It’s not much of a sound bite, though I suspect

for a lot of artists this awkward, run-on description rings true. And perhaps

not only for artists. My brother, for example, drives about the US East Coast

demonstrating and selling engineering products. Wherever he goes he must have a

Blackberry device with him. He can hardly ever escape the office.

This seamless merging of life and work is becoming a pretty common

condition for many people in post-industrial economies. Except that for

artists (as well as independent curators, critics, scholars, etc.) the situation

is especially poignant because allegedly our “creative” and “mental”

labors are part of a vocation or “calling” as opposed to routine, wage-based

work. But is that really true? I mean, after all, most of us have no choice

but to engage in multiple forms of employment just to “pay” for our socalled

artistic careers. At what point does our “free” creative labor—which

presumably negates regulated productive labor—actually slide over into a

kind of full-time affirmative work central to networked capitalism? These

topics are on people’s minds. Curator Dieter Roelstraete has addressed

this play-as-work/work-as-play and the ambivalence it produces by calling

first for realism, followed by a self-conscious attempt at returning to

art its negative, critical function.1 A more sober, less optimistic analysis

is Marion von Osten and Katja Reichard’s video Kleines Postfordistisches

Drama [Small Post-Fordist Drama, 2004]. Have you seen it?

KvdB: No, I haven’t. I’ve just read about the project.

GS: My own collaborative installation I Am NOT My Office (2002)2 fits

in here in a different way, because to create the work I invited a group

of people to imagine what kind of prosthetic enhancement they would

wish to have in order to be able to simultaneously do their “day job” and

also do what they really would like to be doing instead of working (including

making art). I then used their ideas to create miniature models

and drawings, and then the project was installed at the University of

Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art for Critical Mass, an exhibition curated

by Stephanie Smith in 2002. Which gets us back, I think, to your last

1 See Dieter Roelstraete, “A Letter on Difference and Affirmation,” in Art

and Activism in the Age of Globalization, eds. Lieven De Cauter, Ruben De Roo,

and Karel Vanhaesebrouck (Rotterdam: NAi publishers, 2011), 94–99.

2 See http://www.gregorysholette.com/?page_id=37.

question, because I Am NOT My Office was in its own quirky way an attempt

to materialize what Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt describe as

the counterpublic sphere: a fragmented realm of unconscious fantasy produced

by workers in response to the alienating conditions of capitalism.

Almost a decade later, my book Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of

Enterprise Culture used a different approach in order to respond to that

same research problem.

KvdB: What you said about the “mongrel researcher” and everyday

practice in the “fragmented realm of unconscious fantasy” gives

a quite clear indication that your work also includes a permanent

self-questioning. Do you think “work” is an adequate term for your

practice? If I define work as a kind of activity that ensures your livelihood—

as “subsistence-work,” to use a Marxian term—would you

say the activity you just talked about is work in this sense? Do you

make your living by working as a “mongrel researcher”? Or is this

more a privileged realm, enabled by other day jobs? When I visited

you in New York you told me that you sometimes work with galleries,

but you have no close connection to any one gallery, right?

GS: Your right, of course, Karen. As Theodor W. Adorno once quipped:

“criticizing privilege becomes a privilege.” And you’re also correct that

the term “work” in English is often loosely applied to things that we do

regardless if they are waged or not, pleasurable or not. In terms of my

personal finances, therefore, I am fortunate to draw a modest salary from

teaching within the New York City public university system (at Queens

College and at the Graduate Center), and also secondarily I support myself

through lectures and sometimes art commissions. But my point is—

and this is not my unique observation as I suggested before—for us “creative

workers” so-called subsistence work is becoming less and less clearly

differentiated from privileged forms of labor, so that even my taking time

out now to answer your questions could be seen as a kind of work, or as a

playful distraction, or both simultaneously. In other words, it is difficult

to distinguish where one begins and the other leaves off because working

on one’s own career is at best a fuzzy kind of labor. That might not be true, say,

of my brother, because if you where interviewing him instead of me, I suspect

his bosses would most likely consider it extraneous to his salary. Or maybe not?

After all, this is an economy where ephemeral activity generates prestige and “buzz”

that might actually enhance company branding. Still, I doubt this kind of

fuzzy labor “trickles down” to menial jobs that make up so much of the

precarious economy that we are told is the “new normal.”

KvdB: If you talk about “us creative workers,” I

assume this includes more than just the art field. Therefore, I am

curious if the “art field”—as a social field with its own norms,

and maybe even with its own economy, as Pierre Bourdieu describes

it—is still a relevant concept to you. Would you rather talk about

a sphere of precarious creative workers than about the art field?

Or do you still consider yourself to be a player within the art field?

GS: Hmm . . . perhaps it’s a bit like the way Karl Marx uses “capital,”

“money,” “profit,” “surplus,” and other terms in order to investigate a single

phenomenon that has different material manifestations depending on

how he approaches the object of his research: capitalism. So, risking the

loftiness of this comparison, I find I tend to use the term “creative workers”

or “creatives” when referring to the broader arena of cultural production,

and I use “artist” to describe what I and other academically trained

plastic or visual artists do as a subset within that broader arena. To ignore

this definitional specificity is I think a mistake, especially if one is concerned

with questions about changing conditions of artistic labor as I am.

And yet to pretend the “art world” is not a diminutive part of the larger

post-Fordist enterprise economy is simply myopic, particularly if one is

looking at art’s reception or its impact on society.

So, briefly—yes and yes; the issues we are discussing do relate to that

larger category of imaginative social productivity within which “art” is

situated, and, yes, these concerns also have specific possibilities and limitations

for “us”—all of the visual artists, curators, critics, administrators,

historians, interns, students, packers, installers, fabricators, dissidents,

outsiders, and so on who habitually reproduce the symbolic and material economy

of the mainstream “art world.” This is what I describe as art’s

political economy in Dark Matter, and what Oliver Ressler and I take as

our thesis for the exhibition and the book It’s the Political Economy, Stupid

(2013).

KvdB: You are an assistant professor at Queens College in New

York. How do you take all these considerations into account when

you teach in a—if I might say—relatively traditional context of art

education? I would be interested to hear what kind of advice you

would give to one of your fine art students, if he or she were to ask

you for possible strategies to make a living as an artist.

GS: It is indeed a traditional context I teach in. In fact, I was hired as a

sculpture instructor, not a specialist in theory or socially engaged art. My

undergraduate students are often the first in their respective families to

attend college (as I was and remain), and they are typically immigrants

to the US, or the children of immigrants. So as you might imagine, it

raises lots of internal complications for me sometimes. But my approach

to teaching is both pragmatic and idiosyncratic. As for the practical part

I am always upfront with my students about the difficult conditions we

artists find ourselves in today. I never sugarcoat the art “profession.” But

just as my friend and former professor Hans Haacke explained to us back

in the late 1970s, one must search out every possibility to make one’s

work visible, and the same goes for finding meaningful employment. That

advice, too, is bound to bring about its own contradictions. Nevertheless,

for people not living on trust funds or grants—and that includes all of

my students—“political correctness” must sometimes take a backseat to

survival. So this past year, as chair of the MFA program, I specifically

focused the semester on how to sustain oneself as an artist by inviting

guest speakers with wide-ranging approaches to this challenge, including

the graphic artist Josh MacPhee, whose online, worker-owned cooperative

Justseeds sells inexpensive, politically focused print art. At the same

time, I have to acknowledge that as Vladimir Mayakovsky’s friend Viktor

Shklovsky insists: being an artist requires the energy of delusion. Well,

OK—perhaps it is more akin to embracing delusion without becoming delusional?

And maybe art comes down to appreciating the thinness of

the line separating those two possible states of being?

KvdB: Sounds like continuous struggle! But being an artist seems to

be attractive anyhow. Moreover, it seems it has never been so attractive

as it is today. The number of young people who want to be artists

increases constantly. This leads me to my last question: Your work is,

as you mentioned, about changing the conditions of artistic labor,

and I would say your work is characterized by a politically active approach.

But to what extent do you think art is an essential approach

in the field of political activism?

GS: The research I did for Dark Matter strongly indicated that an unprecedented

number of people (at least in the US, UK, and Germany) claim

to be artists these days—though I am not sure it is only young people. So,

yes, being an artist is clearly attractive. Or has been attractive for some

time. But why? I mean, considering that it has always been a precarious

occupation—or better yet, vocation—and that today, after several decades

of deregulation and privatization, it is even more so. At least this is true in

the US where the lack of grants, jobs, health insurance, reasonable spaces

in which to live and work (in key cities), and, of course, student debt that

can reach well over $50,000 makes studying and becoming a “professional

artist” appear like a ridiculous pursuit. (I understand that sometimes from

a European perspective it is less challenging to grasp our situation.) But

would I describe it as a fun struggle? Maybe—in a curious, counter intuitive

way. Or perhaps the thorny pleasures of being an artist somehow relate

to the way a hyper-entrepreneurial society insists on creative risks and

constant innovation? After all, it was a piece in the Washington Post a few

years ago that asserted the “MFA is the new MBA”!3 That kind of hype

may make such insecurity seem almost sexy. Or at least it may have made

it so before the “society of risk” went over the cliff. In fact, I have been

wondering if the stats are still going in the same direction since 2008.

3 Philip Kennicott, “Daniel Pink and the Economic Model of Creativity,”

Washington Post, April 2, 2008, http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2008-04-02/news/36846243_1_fine-arts-left-brain-mba.

What about politics and art? As far as I am concerned, art is always

political and always communal. People like Haacke made this clear to me

long ago, as did having such friends and collaborators over the years as Lucy

Lippard, Leon Golub, Carol Duncan, Andrew Hemingway, Martha Rosler,

Janet Koenig, Oliver Ressler, John Roberts, Blake Stimson, Brian Holmes,

Gene Ray, Gerald Raunig, Marc James Léger, Krzysztof Wodiczko, and

Olga Kopenkina, as well as the many brilliant people I have worked and collaborated

with over the years in such collectives as REPOhistory, Political

Art Documentation/Distribution, and, most recently, the GulfLabor

Coalition. Still, what is key, I think, is differentiating art made politically

from art that only seeks to represent politics. And this is even more important

today since art has apparently taken a “social turn,” to cite my colleague

and friend Claire Bishop. So with all this talk about social practice and

artistic activism, even within major museums (though it is really just “talk,”

as far as I can tell), I am compelled to quote Jean-Pierre Gorin, another former

professor of mine, who once said the point is not to make political art

but to make art politically. That, however, does not always mean engaging

with “politics” head-on. Most recently, for example, I have been exploring

the way cultural production itself—in my case this means artistic labor and

its related conditions of production—meshes with broader battles over liberty,

democracy, and economic equality. I do this through my writings and

research, and also through my art. Sure, sometimes this means addressing

political issues directly—and yet “politics” also means engaging in processes

of collaboration and/or exploring my own or other people’s fantasies of liberation

or even outright “escape” (both are visible in such projects as I Am

NOT My Office, Fifteen Islands for Robert Mosses (2012), Imaginary Archive

(2010–), and, most recently, the graphic novel Double City). So I suppose for

me making art is about adding a small, sometimes personal and sometimes

communal, chapter to that long, winding history of struggle “from below.”

He is NOT his Studio: Looking at Greg Sholette

By Jon Fine jonfinearts.com

The term ‘Postmodernist’ should not be a dirty word, a description whose mere mention causes many an eye to roll. While its definition can be ambiguous, and stubbornly perplexing in its playful indeterminacy, it is occasionally the best description for a comprehensive body of work. The art of Greg Sholette, on display in his exhibition Selected Projects, is postmodernist, or, perhaps more accurately, ‘post-studio.’ His varied, complex work forcefully engages itself in conversation with the latter-half of twentieth-century critical theory. It conspicuously shrugs off any pretensions to ‘high art’ by synthesizing art practice with social commentary, sweeping past the barricades Modernism once established between art-making and life, injecting considered aesthetics into the quotidian. It denies the privileged autonomy, and subsequently, commoditization, of the ‘art-object’ and ‘author-artist.’ And, most importantly, it dismisses the imposition of a systemized aesthetics. Therefore, Sholette’s works, such as I am NOT my office and the Lower Manhattan Sign Project (executed by the group REPOhistory), are best analyzed through the comprehensive lens of established Postmodernist discourse.

In I am NOT my office, Sholette, like pop artists before him such as Roy Lichtenstein, utilizes the medium of ‘low-art’ at the core of his work. In this particular instance, Sholette crafts ‘action-figurines’ based of the “sub-cultures of amateur art-making,” which include sci-fi and action movies, comic books, website design and home video. I am NOT my office explores the potential relationships between the work of the trained ‘high’ art professional and the informal work of the amateur. Sholette contends that, despite its marginalization, the subcultural ‘dark-matter’ work of the amateur “maintains a symbiotic relationship with the (art) world that is both creative and economic.” “Sub-culture art” therefore exists in a state of semi-autonomy: it is both valid in its own right and as an essential supplement to the development of contemporary art.

In I am NOT my office, Sholette, like pop artists before him such as Roy Lichtenstein, utilizes the medium of ‘low-art’ at the core of his work. In this particular instance, Sholette crafts ‘action-figurines’ based of the “sub-cultures of amateur art-making,” which include sci-fi and action movies, comic books, website design and home video. I am NOT my office explores the potential relationships between the work of the trained ‘high’ art professional and the informal work of the amateur. Sholette contends that, despite its marginalization, the subcultural ‘dark-matter’ work of the amateur “maintains a symbiotic relationship with the (art) world that is both creative and economic.” “Sub-culture art” therefore exists in a state of semi-autonomy: it is both valid in its own right and as an essential supplement to the development of contemporary art.

Yet, to call I am NOT my office ‘pop’ would be disingenuous; the intrinsic commentary embodied by Sholette’s work moves beyond a simple flattening of the ‘high-low’ art distinction. Despite its revelatory status, pop art still adhered to academic tenets of composition and beauty, all of which was ‘channeled’ through the conduit of the professional artist. Artist and critic Mary Kelly, in her postmodern piece “Re-Viewing Modernist Criticism,” negated the so-called privilege of those artists uniquely ‘qualified’ to produce art deemed significant. She claimed that rigid adherence to any critical principle ignored the time-tested Kantian ideal that “genius is the mental disposition through which nature gives rule to art…no definite rule can be given for the products of genius, hence originality is its first property.” In this context, the media of I am NOT my office theoretically moves beyond the substance of ‘pop’ in its suggestion that so-called amateur art forms and artists, no less than professionals, can be sources of functional creative energy, originality, even genius. I am NOT my office champions unbridled self-expression, and gleefully eschews pop’s reliance on a set of trained aesthetics. It revels in its declaration that there is no monopoly on creative labor.

I am NOT my office also demonstrates an indebtedness to the postmodern ideal of ‘process,’ an idea that strict ‘objecthood’ need not be the sole determinate of a work’s finality. Robert Morris articulated this concept in the text, Notes on Sculpture 4: Beyond Objects, and in his ambitious project, Box with Sound, which included an audio recording of the artist working on the box-structure that would be identified as the “finished” product. Sholette employs a similar strategy, bringing literal art-practice to the forefront of the viewer’s consciousness. At the foundation of I am NOT my office is a questionnaire posed to office workers, asking them to describe ideal super-powers that could aid them in their professional life. From the results of these questionnaires, Sholette envisions and constructs his ‘meta-object’ figurines. These models are not displayed as free-standing, autonomous objects (final pieces); rather, they occupy space alongside comic-like ‘process collages.’ These ‘process collages’ reveal a step-by-step methodology that incorporates the literal text of the questionnaire alongside the pictorial development of its corresponding ‘meta-object.’ Process is emphasized over product, creative labor over ends. The finalized ‘meta-objects’ do not function, or engender meaning, as entities independent from the actual conditions from which they were produced. Instead, they exist, like the physical box in Morris’ Box with Sound, only as the ‘end’ of art-practice, a single element of the piece’s ‘text.’ The result is a work that rejects singular autonomy (as well as singular authorship). I am NOT my office reveals, in an intentionally low-art fashion, the oftentimes confusing and indeterminate segmentations of cooperative multi-tasking and responsibility.

In Sholette’s collaborative, public piece, the Lower Manhattan Sign Project, the artist continues his defiance of academic conventions. Like I am NOT my office, the Lower Manhattan Sign Project denies singular authorship and, subsequently, a fixed place in the history of culture; as a collective effort, it neutralizes the effect of Foucault’s ‘author-function,’ i.e. the categorization and limitation (individualization) of a work’s meaning as relegated by the context of its author. More importantly, however, the project utilizes the ‘textual reading’ of public space in place of a formal exhibition space. Why does this matter?

In essence, art forms are subjected to the mutability of social context and their relationship to other proximate works, or ‘texts’ (i.e. forms of cultural production which produce meaning). Under Modern considerations, as Mary Kelly again explains, the literal, unifying element between these otherwise independent works is the exhibition. The exhibition encompasses individual art-texts within a particular social framework, or context, and, through this ‘inter-textual network,’ produces significant meaning over and above the inherent. Like the Soviet film ideal of ‘intellectual montage’, one piece of art informs the meaning of the work hanging next to it by its sheer juxtaposition; the museum structure, with all of its cultural implications, affects the reading of all the texts it encompasses.

By moving the work outside the museum/exhibition, the area previously proscribed for ‘art-texts,’ Sholette confronts the question offered by Jeffrey Skoller, “In what ways do the meanings of social histories and issues change as they enter into the institutions of culture, from the museum to the university to the streets of a specific community?” In the instance of the Sign Project, the public space becomes the exhibition space and the arena of comparative discourse. Rather than engage other, proximate, literal texts in a discourse regulated by the formal exhibition, the signs organize their meaning in relation to the ‘text’ of the public environment, where a considerable intersection of variable and changing discourses occurs. Significance in the project is therefore not derived from a singular and established relation to other art ‘texts,’ but in its correlation with the surrounding historical, social and cultural ‘text’ of the community. As its surrounding environment changes, so too does its meaning.

Sholette is the feisty, contemporary, post-consumerist embodiment of the old constructivist slogan, “art into life, and life into art,” a Rodchenko for the twenty-first century (sans the socialist optimism). His work denies the prominence of the art-academic, the domineering status of the formal exhibition, and the Modernist maxims of armchair theorists. He subverts the cherished (capitalist) ideal of the self-sufficient art-object, creating socially-charged works whose elements are spatially, materially and pictorially fragmented and heterogeneous, yet textually inseparable. He exalts the amateur art-maker and the citizen participant as fundamental to creative action, artistic and political. And at every step of the way, Sholette resists a fixed identity, his work undercutting the systems of commoditization, celebrity and ownership that have come to dominate and define the still Modernist-dependent art market. Oftentimes playful, occasionally ambiguous and sometimes confusing in its indeterminacy, Sholette’s studio-independent work is (in)definitely postmodernist.

________________________________________

Whitehot Magazine

whitehot | May 2012: In Conversation with Gregory Sholette

For his project Fifteen Islands for Robert Moses (currently on view at the Queens Museum of Art), Gregory Sholette asked 15 artists, known for their work in social activism, to come up with an idea for an island that could be added to the panorama of New York City installed at the Queens Museum. The panorama is the largest scale model of a city in the world. It includes every building that exists in the five boroughs. It was commissioned by Robert Moses for the 1964 World’s Fair and took over 100 artists 3 years to build.

Fifteen Islands for Robert Moses includes projects by Hana Shams Ahmed, Brett Bloom, Larry Bogad, Marc Fischer, Aaron Gach/Center for Tactical Magic, Libertad Guerra, Dara Greenwald, Marisa Jahn, Karl Lorac/Themm!, Ann Messner, Ted Purves, Rasha Salti, Dread Scott and Jenny Polak, Jeffrey Skoller, and Nato Thompson. Models of these islands were built by Gregory Sholette and installed in the panorama. On view through May 20, 2012.

Gregory Sholette was a member of Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D: 1980-1988), and REPOhistory (1989-2000), both artist groups that were once active in organizing politically-inspired shows in New York. He is the author of Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011), a book that explores the role of the 99% of artists who do not live off sales of their work. He is also a member of The Institute for Wishful Thinking, an artist group started by Greg and Maureen Connor in 2008 with a group of then MFA students,

Patty Harris: Given Robert Moses’ legacy, his domineering, overarching plan for developing New York City and the public resistance to it, why is this show called 15 Islands for Robert Moses?

Gregory Sholette: I wanted to make a reference to the fact that Moses was the one who commissioned the panorama for the 1964 World’s Fair. I wanted to also, in a roundabout way, pay homage to the anonymous model-makers who constructed the original panorama. Thus the title is somewhat tongue-in-cheek, “Fifteen Islands for Robert Moses.

Harris: Why islands?

Sholette: I had a very perverse reason for this. I wanted to ask people who specifically were engaged with, or had written about, social-practice art to then come up with an island because, in my mind an island, or isolated landmass, is a direct metaphor for detachment and exactly the opposite of social engagement. There’s some perversity in that.

Harris: Along those same lines, if the fabric of city life is interdependent and social, what is the correlation between individual desires and how they shape the public experience of the city?

Sholette: They always do shape the fabric of the city. But desire doesn’t necessarily come from individuals; it’s often collectively produced. Part of it is a feedback mechanism between the city as a complex machine that generates pressure on the collective to have certain fantasies and materializations of the urban evironment. It’s also a place where that feedback mechanism can break down and create spaces for interesting, alternative zones of fantasy and possibility. I think one of the things that’s happened since I’ve been in New York since 1977 is that those little gaps and spots and undefined urban places have really closed down and sealed up thanks to the forces of gentrification, deregulation, privatization, and of course constant surveillance. They’ve been welded shut. In going back to the Fifteen Islands project, you might say I was trying to pry open that space and insert a different possible reading of the landscape of the city.

Harris: Do you think that the closure of those kinds of spaces of alternative possibilities has had an adverse effect on the social life of the city?

Sholette: I guess it would depend on where you were coming from. If you’re a real estate agent, banker, insurance person, I would say it has not had a negative effect. It’s actually had a beneficial effect to allow for the stabilization of all kinds of things. Crime has been reduced, etc. But it also means everything is much more regular and more typically middle-class. People raise their children here, they can go to school here, they jog in Central Park without worrying about tripping over junkies. All of those details have been beneficial to what we sometimes call FIRE – Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate industries, who dominate the politics of the city. If however you’re coming from a different perspective such as that of an artist, a musician, or perhaps an educator who wants to make people think critically, or are a person who lives in a part of the city that’s being gentrified, or someone who does community work for any number of constituencies at the small end of the political spectrum, those people looking at that situation might say no. The social life of the city is no longer as open to the idea of the commons. It’s actually been quite detrimental having these zones of possibility, fantasy, and even let’s call it resistance, closed down and sealed up.

Harris: There seems to be an element of utopia in this project. Do you think that individual ideas of utopia could combine to create a greater social experience for everyone?

Sholette: I’d like to think that that’s possible. I think that kind of speaks to what has been going on since the beginning of Arab Spring. As far back as the Green Revolution in Iran and then more recently in Tahrir Square in Egypt, and in Tunisia, and the resistance to Scott in Wisconsin, and up to Occupy Wall Street, I think that all of these have some of what you’re talking about. They tend to be individuated movements towards a kind of different future or possibility or utopian moment rather than being merged into one big idea of utopia. They retain individuality but are combined spatially rather than ideologically. I say this because it contrasts with early 20th Century Modernist ideas of utopian thinking in which you had to subscribe to a regime that called itself utopia. If you deviated too much, you really weren’t part of it. Here the deviation seems to be part of the moment. I think that’s quite interesting and quite unique. And perhaps some of that “diversity within unity” is also expressed by my project Fifteen Islands.

Harris: Do you think there is a fascination with a world in miniature in itself?

Sholette: It was Claude Leví-Strauss, the anthropologost, who said that he believed that miniaturization was at the very heart of all aesthetics. He made the point that when you look at a monument, you think at first, ‘Oh, it’s huge.’ Actually, in a sense, it is a kind of miniature version of some far grander thing like a boulder or entire mountain. I think it’s an interesting take.

Harris: How is this project related to your recent book, Dark Matter?

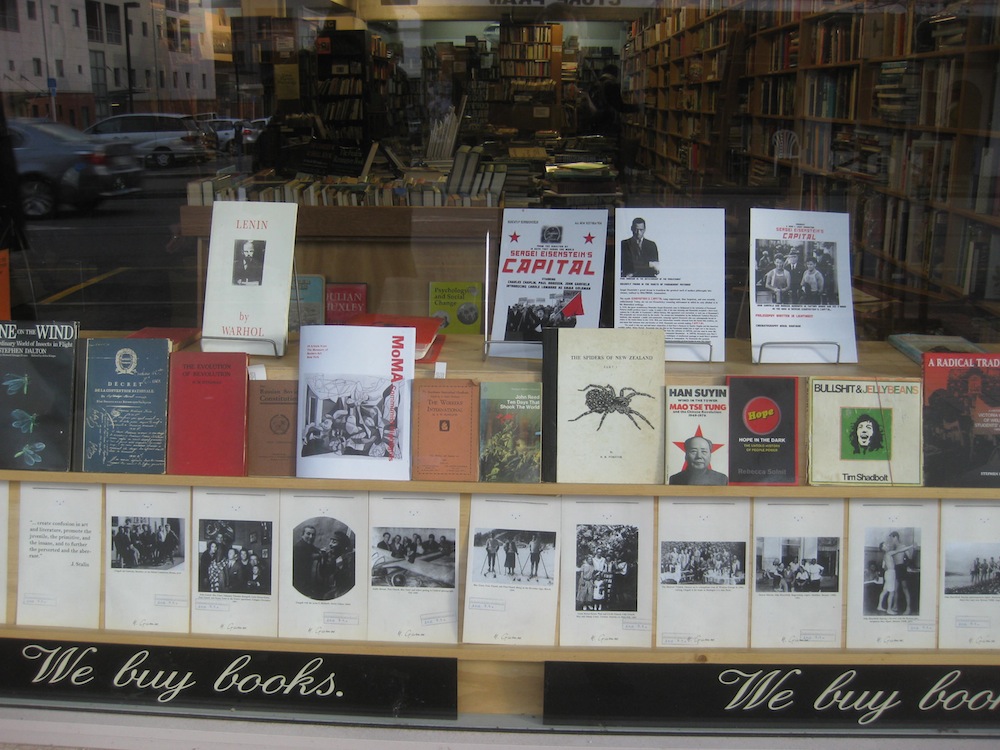

Sholette: It’s an interesting question. It does actually relate in several ways. The most important way for me is the kind of artistic practice that I think it represents is fairly off the radar screen of the mainstream artworld. It’s not really considered art. We’re now talking about the many unknown and invisible people who produce things like the panorama which is a professionally fabricated miniature model, perhaps the largest in the world, but it is nevertheless much closer to the kind of amateur diorama builder or scale-train enthusiast than it is to the world of painting and sculpture. I got my start after art school making a living in a model-making shop. I also ran a model-making shop for awhile in the Gowanus area. So the project draws on that set of skills but also my experience of working in an “artistic” mode located outside the parameters of “fine art.” More importantly there is also an enormous number of people in the world who do this kind of work purely for the love of creating miniature worlds. Sometimes the work they do is so profoundly skilled and interesting that it would stand up very well next to most of the things that you see in contemporary art galleries. That pretty much illustrates a part of my thesis which states that there is an enormous amount of creativity that takes place that the art world simply does not and cannot acknowledge. To acknowledge it would undermine its own privileged concept of artistic “value.” So you might say the model-making is an homage to this dark matter amateur productivity.

Harris: How is this project related to your work with The Institute for Wishful Thinking?

Sholette: Sure there is some relationship in so far as The Institute for Wishful Thinking asks people “What would you like?”, and “Can we fulfill your desires?” But Fifteen Islands really relates back more specifically to a project I did in 2005, or a little earlier, called I Am Not My Office. At the time there was an ad campaign by Microsoft saying, “I am my office,” with very hip looking young people. This was the catch line. The idea being that with Microsoft technology you can become a virtual office. I borrowed it and added ‘not.’ I asked a series of questions to a group of people some of whom were artists, others art historians, and some office workers with no art world connection. My question was this: If you could have any sort of superpower or prosthetic extension, that would allow you to fantasize while you’re at work about the things you really want to do, what would it be? Then I selected some of the answers and I fabricated models, kind of like action figures, and then exhibited this as an installation for the Smart Museum in Chicago. That’s really the origin of the concept behind Fifteen Islands for Robert Moses.

Harris: What do you think Robert Moses would think of your project?

Sholette: Not knowing his personality, I think he would ironically find it amusing. I’m guessing. Maybe a couple of pieces would hopefully rub him the wrong way politically. For example he might object to the “model” of an imaginary independent Palestine as envisioned by Rasha Salti in the form of speeding subway cars — both utopian and lonely at the same time — or Larry Bogad’s idea of Dunkin’ Island where bankers are publicly “waterboarded.” Because the works range from very humorous, frivolous and playful to more serious. Only if the islands were seriously considered for construction would he then probably find it quite impossible and upsetting. But of course, his master plan of New York City was once just a fantasy as well, so who knows?

________________________________________

art:21

Inside the Artist’s Studio | Gregory Sholette

Gregory Sholette is a New York-based artist, writer, and founding member of Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D: 1980-1988), and REPOhistory (1989-2000). A graduate of The Cooper Union (BFA 1979), The University of California, San Diego (MFA 1995), and the Whitney Independent Studies Program in Critical Theory, his recent publications include Dark Matter: Art and Politics in an Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011); Collectivism After Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after 1945 (with Blake Stimson for University of Minnesota, 2007); and The Interventionists: A Users Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life (with Nato Thompson for MassMoCA/MIT Press, 2004, 2006, 2008), as well as a special issue of the journal Third Text, co-edited with theorist Gene Ray on the theme “Whither Tactical Media.”

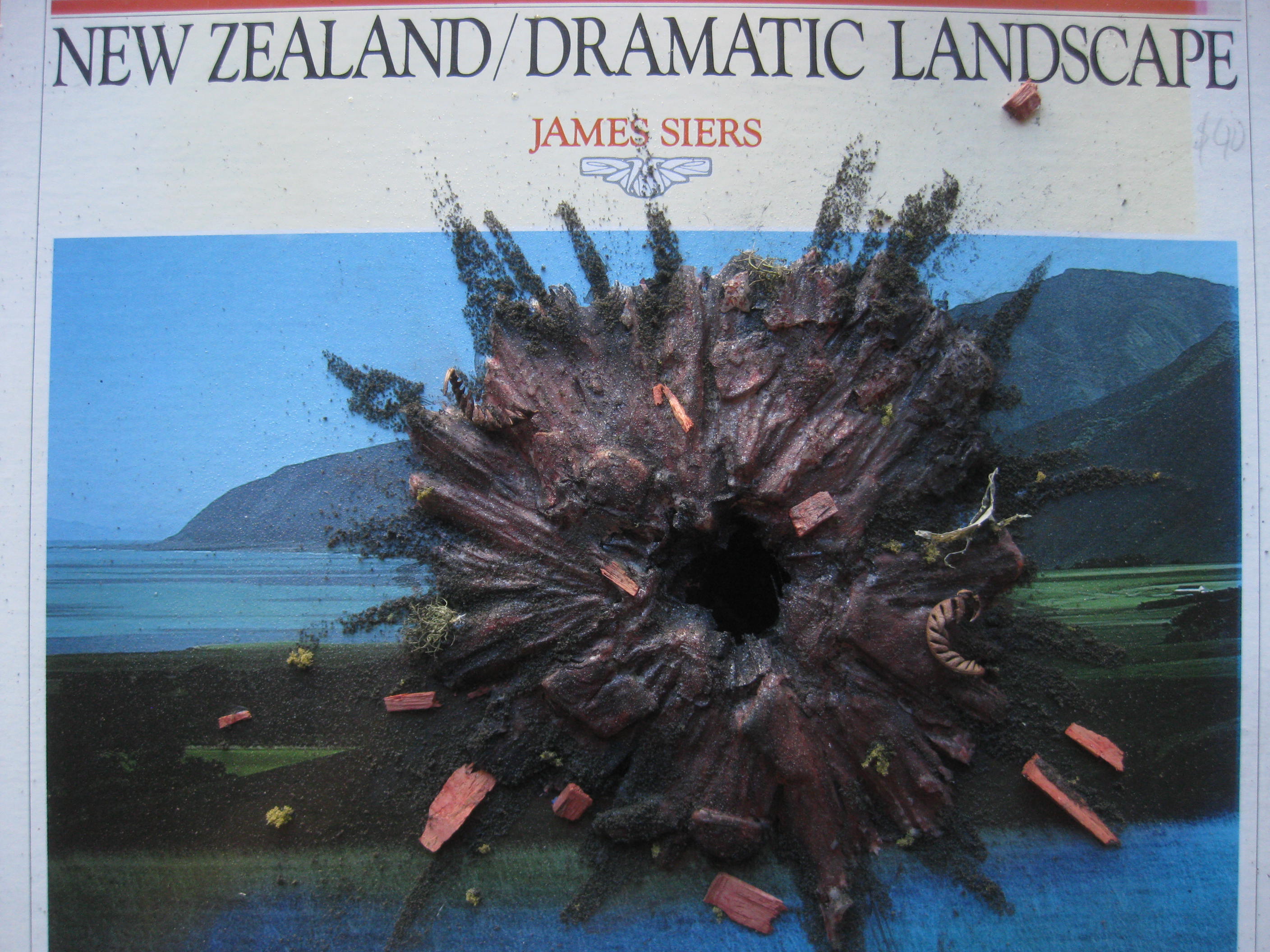

Sholette recently completed the installation Mole Light: God Is Truth, Light His Shadow for Plato’s Cave, Brooklyn, New York, and the collaborative project, Imaginary Archive, at Enjoy Public Art Gallery in Wellington, New Zealand.

Sholette is Assistant Professor of Sculpture at Queens College, City University of New York (CUNY), a visiting faculty member at Harvard University, and teaches an annual seminar in theory and social practice for the CCC post-graduate research program at Geneva University of Art and Design.

Gregory Sholette speaks about “God Is Truth and Light His Shadow” at Plato’s Cave, NY, 2010

Being familiar with the angle of Sholette’s work, I picked up Dark Matter and read the Preface and Acknowledgments. Yet before I was done with page 1, I got up to sharpen a pencil. You want to give this book the appropriate attention; it will alert your conscious while enlightening you on the structure of our creative universe. Dark Matter is a metaphor for “amateur, informal, unofficial, autonomous, activist, non-institutional, self-organized practices – all work made and circulated in the shadows of the formal art world, some of which might be said to emulate cultural dark matter by rejecting art world demands of visibility, and much of which has no choice but to be invisible,” in Sholette’s words. The mechanics, tactics, and power of art activism and politicized practices are unveiled with direct references, drawing out the behind-the-scenes of the art world within today’s economic landscape.

It’s an honor to present Gregory Sholette to you today. Sharpen a pencil and pick up Dark Matter.

Georgia Kotretsos: Currently you’re involved with the self-declared artists-in-residence for the US government, the Institute for Wishful Thinking (IWT), which believes that the community of artists and designers possesses untapped creative and conceptual resources that could be applied to solving social problems. Please, tell us about your contribution specifically to this project and your latest work.

Gregory Sholette: In 2008, the noted Hungarian curator Dora Hegyi was seeking work for the 8th Periferic art biennial in Iasi (pronounced “Yash”), Romania, that she was organizing around the theme of “Art as Gift.” Because of my writings on gift economies and informal art, she contacted me. I made her some homemade pizza. I told her about the book I was working on that would focus on the political economy of art, especially that vast amount of invisible labor and imagination that the art world is secretly dependent upon (more on this below). The next day, I contacted the artist Maureen Connor, who is my colleague at Queens College and within no time, Maureen proposed the IWT: an ersatz institute whose primary aim is to provide gifts – useful, secret, or fantastic gifts – directly to those invisible souls who labor behind the screen that separates the public exhibition from its managerial apparatus. Who are these people? Typically, they are young, recently graduated, or out of work artists, art historians, educators, and cultural administrators. And if we think of the screen or curtain as the legendary fourth wall in the theater, except that here it is a white-on-white sheetrock wall, then we are not supposed to notice that behind this partition lurks a shadowy species of creative dark matter. At one meeting, we compared this other realm to the Freudian libido and wondered what kind of fantasies of generosity it would call out for. In Iasi, our attempted emancipation led to unexpected outcomes, but first let me tell you a bit more about IWT.

In many ways, the IWT concept sprang naturally from the mutual interest both Maureen Connor and I share in what might be called the imaginative disruption of everyday life by both artists as well as non-artists. For example, Maureen’s earlier project, Personnel, investigated the “attitudes, needs, and desires” of office staff where she was invited to create an artwork. One manifestation of Personnel transformed the so-called “personal” space of cubicle workers into a boudoir, and another into a campsite. IWT also resonates with my work, in particular the 2002 installation I am NOT my Office, in which workaday fantasies from the practical – I want multitasking centipede limbs or arms like Shiva – to the maniacal – a flying ear that gathers information on office politics – [are rendered] into a series of drawings and “action figures.”

But the real evolution of IWT began when we invited several talented MFA students from Queens College to join us and brainstorm about how to satisfy the fantasies of people we had never met on the far eastern side of Romania. The upshot was to create a website where the Periferic 8 biennial staff could log on and type in the kind of gift they wanted us to fulfill. And there were three categories of potential gifts: 1) a practical gift, 2) a fantastic gift, and 3) a secret gift. Ultimately we brought as many fulfilled desires as we could transport to Iasi including: a modest library of books on art and theory; some photographic materials that were difficult to get in Romania; several felt sleep masks stitched together by agent Kirby as a kind of substitute for a work by Joseph Beuys that the Periferic organizers could not afford to borrow for display; an onsite gift of labor performed by agent Mahler that involved spackling and prepping exhibition walls; a song written and performed by agent Rubin which was gifted to a Periferic staff member who was secretly in love with someone; and finally a stuffed “Kermit.” But for a year, this gift request remained a puzzle to us. On the website someone from Iasi secretly asked for a Kermit. But what did it mean? Was Kermit Romanian slang perhaps? Or was it a reference to a certain green television character as we immediately assumed? Did people in the “Eastern Bloc” actually grow up watching Sesame Street? Since it was a “secret” request, we did not have the option of asking more. Instead, we collectively decided that fulfilling certain gifts gave us license to be imaginative, even a bit subversive. In response to the Kermit request, agent De Felice stitched together a batrachian sock puppet, carried it with her to Iasi for the opening, and after walking around the exhibition for about an hour, a Periferic staffer finally came over, accepted the gift, publicly embracing her desire a secret no longer.

To be fair, we also encountered a degree of skepticism from some of the artists in Romania. And not all of it was unjustified, at least on the surface. I do think in retrospect the idea of bringing “gifts” from the wealthy United States to the struggling economy of a former socialist nation seemed a bit cheeky. This was an insight we needed to have more discussion around, as agent Pavlou thoughtfully suggested at a later meeting. At the same time, few in Romania probably realized just how precarious our living circumstances are sometimes in a place like New York City, especially for recently graduated MFA students, like most of the members of IWT. Anyway, [here is a link] for more on this first IWT project in Iasi.

IWT produced its most recent project, entitled Artists in Residence for the US Government (self-declared) for Momenta Art, a not-for-profit space located in Brooklyn. The mission of this project was to “increase understanding of the art making process and how it can contribute to society as well as encourage policy makers and the general public to think of artists as potential partners in a variety of circumstances.” I suppose you could say that at a moment when actual governmental and social infrastructure has been decimated after thirty years of privatization, deregulation, and economic contraction at the public level, the IWT seeks to make transparent one of the last remaining sources of untapped collective value: the social imagination of those thousands upon thousands of academically trained artists and art students who constitute an invisible army of precarious, over-educated surplus laborers. Like a redundant missing mass, this shadowy creativity is brimming with the possibility of either radical change or precipitous regression. This ambiguity seems especially striking today in the icy grip of the aptly named “jobless recovery.” I will discuss this vibrant dark matter more below, but for now you asked me about my role in this latest project, Georgia, so let me finish here by saying that along with brainstorming ideas with IWT and helping with the physical installation at Momenta, I also introduced our group to THEMM.US, a hitherto unknown collective entity. And although politically unpolished and a bit ribald, their odd little sculptures and experimental thrash songs “for government agencies” were featured on one wall of the exhibition. Funny thing is I am even thinking about collaborating with them on some upcoming project.

The mission of the IWT is ongoing and we encourage new proposals (via our website) that we hope, wishfully as well as concretely, will develop into a new model of support for artists in which they are paid to consult with policymakers and elected officials.

Along with Maureen and myself, The Institute for Wishful Thinking consists of the artists (who are also Queens College graduates): Susan Kirby, Nathania Rubin, Andrea DeFelice, Matt Mahler, John Pavlou, Bibi Calderaro, and Tommy Mintz.

GK: Studying your case, I realized that you do not simply have a studio practice but you rather have an art life which consists of educating young minds, being a practicing artist, a writer, an administrator, an organizer, an initiator, a participator, an activist, and a thinker who looks forward, produces ideas, and generates knowledge. The North Pole is taken, so where do you and your elves operate from?

GS: I am my own “elf.” That is why I often work small, turning out only a few art projects a year. But you want to know what Geppetto’s little red workshop actually consist of? It’s a 5×12 extra room in my Inwood apartment, plus my MacBook Pro loaded with Photoshop. Seriously, I am not opposed to outsourcing the fabrication of artwork when its necessary, but I like making things myself, it’s a powerful anecdote to my research and critical writing, even though one is a direct extension of the other (at least to my mind). I have had assistance with a few projects however, and extensively so with my twin websites including from Andrea De Felice mentioned above, as well as Yue Zhang, William Thompson Harris, and the multi-talented Matthew Greco.

GK: If we were to visualize a pyramid where its tip is occupied by mainstream successful artists, does this mean that what’s right beneath the tip could all be dark matter? Do activists, struggling and failed artists, hobbyists, and amateurs all fall under one homogeneous enormous category or since art activism has continued to earn art historical ground, it’d be best to place it between mainstream artists and everybody else left in the art world?

GS: Thanks Georgia, this is a crucial question and I hope it is acceptable to ask people to read my new book, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011), rather than only download my older essays about dark matter from the Internet. Of course I am plugging my own little capitalist endeavor here, but also significantly, the concept of dark matter or missing mass has evolved over the last ten years. Now when I use the term dark matter, it is meant to invoke two different registers at the same time: one abstract, the other very much concrete. But then thinking in contradictions is something I have learned above all from being an artist.

Dark matter is merely a metaphor, the best I could find, for describing something that has an effect on the mainstream cultural world, but is largely unseen by it. First, think of the art world as an economy with both symbolic and material dimensions. Within this economy, dark matter is both present and absent, detectable at one level, but lacking its own discourse, and therefore all but unnameable. However, (and here comes the contradictory bit), dark matter also describes something concrete, something that has measurable reality, something like the way an offsite archive of key documents adjudicates meaning from afar. So yes, you’re correct: this “missing matter” does includes the various informal activities you mention like amateur and hobby crafts and so forth. But it also incorporates what art historian Carol Duncan once described as the glut of artists who never reach visibility. This, Duncan insisted, was the “natural” condition of the art world. What I hope my research and writing begin to do is to intervene in this so-called natural economy by unsettling and possibly re-politicizing the realm of cultural production itself. Ok, that is grandiose. But what I am trying to get at is that like almost everything else today, art is the outcome of social production. And this fact is diametrically opposed to art’s mythology that revolves around the isolated artistic genius working alone in her studio. Most of us know this is a fallacy. Still, we allow the economy of the art world to divvy up this socially produced wealth like so much “real estate,” as if only a handful of gentry grew above an ever-shrinking commons. Whether this other collective productivity is visible or is hidden, or slides in between both those states of light and darkness, is less the point than to recognize that dark matter production runs through all of these institutions and discourses like a multitude of veins in a piece of marble. That is why the image of the pyramid is less useful or accurate for fully describing art’s political economy (even though admittedly, the towering needle with its broad base or long tail is still a powerful and intuitive representation of the unequal recognition most artists feel as they contemplate the mainstream cultural landscape and their assigned place within it). Therefore even before one begins to speak about “political art,” or “interventionism,” or “relational,” or “dialogical,” or “participatory,” or “philistine” aesthetics (to cite respectively: Lucy R. Lippard, Nato Thompson, Nicolas Bourriard, Grant Kester, Claire Bishop, or John Roberts and Dave Beech), one must first understand there is a political struggle at the level of production. Or as Zizek quipped, “It’s the political economy stupid!”

GK: What are your thoughts on the transition of dark matter from the streets, the web, and the wider periphery to the museum, the podium, and the establishment?

GS: In terms of the apparent recognition of a certain previously unacknowledged informal art, well, it’s just not the case that street art and home crafts have never been part of the art world. I would argue that such practices have always been not only present, but also influential on artists, but simply not named as such. What has happened in recent years is [that] this shadowy archive of heterogeneous messy sentimental everyday imagination is becoming inextricably more visible. For example, look at the incredible art world success of the Young British Artists in the 1990s. One can clearly see the YBAs directly borrowed from this realm of informal, vulgar, and street aesthetics, as if secretly recognizing that [this] invisible mass was on the rise. However, their response was to snip bits of dark matter off, incorporate this into their art, and tack it to the walls of the white cube. Over a decade later, with greater advances in bandwidth and Internet technology, but also an ever-increasing number of people claiming to be artists (see Chapter 5 of Dark Matter: “Glut, Overproduction, Redundancy!”), this other social production is more and more simply representing itself! I suspect we are on the verge of a kind of P2P art world that will run parallel to that of the one familiar to us now. Will this be a significant advance, politically speaking? Will the structural disequilibrium of culture be overturned and redistributed more equitably? In other words, will art world real estate – its assets and symbolic power — be transformed back into something of a commons (though I doubt it ever was that)? These are the critical questions my book seeks in the end to raise with regard to so-called dark matter. And all the while, I am very cautious. Cautious about the mainstream museums and art collectors who are interested in street art, cautious about the way certain corporate interests are salivating over the rise of consumers who produce their own creative content, aka Prosumers, and cautious about the new interest in “social practice” art. Recalling the way “political art” in the United States became a fleeting fashion in the art world of the late 1980s and early 1990s, my antennas of apprehensiveness are twitching madly these days. Let me just cite one quote from Wired magazine that I use at a crucial juncture in my new book:

Previous industrial ages were built on the backs of individuals, too, but in those days, labor was just that: labor. Workers were paid for their time, whether on a factory floor or in a cubicle. Today’s peer-production machine runs in a mostly nonmonetary economy. The currency is reputation, expression, karma, “whuffie,” or simply whim.

— Chris Anderson, editor of magazine Wired, “People Power Blogs, user reviews, photo-sharing—the peer production era has arrived,” Wired, July 2006.

What is invigorating therefore about this explosion of the shadow archive is that it is filled with potentially positive elements and processes like gift economies and P2P productivity. What is not good is that it is already being selectively filtered for incorporation into the values structure of capital. That is one place where a political struggle must be waged. But what is equally or perhaps even more of a concern in the short run is that what I am calling dark matter is also permeated with reactionary, regressive elements. The Tea Party or the Minutemen militias are but two examples. And no doubt there are versions of these anti-democratic tendencies even within our own artistic ranks.

GK: Asking you all the way from Greece, what does economic crisis produce? What have we learned from the past?

Syntagma Square, Athens, Greece, May 25th 2011: Taking the lead from Spain, thousands of people gathered at Syntagma square on Wednesday to protest against austerity measures, responding to a grassroots Facebook campaign. The crowd sings the Greek National Anthem.

GS: For us as artists and cultural workers, it comes down to developing a viable, democratic, counter-narrative that, bit-by-bit, gains descriptive power within the larger public discourse. That said, we first must begin here with us artists, and what we do, and how we create by gaining an understanding of the potential transformative power of this missing creative mass that we are talking about and that we also embody. We need to ask how to use this vibrant inert mass to intervene within the political economy of culture understood as an everyday form of production.

And that’s a wrap!

________________________________________

art:21

Artist, scholar, organizer, and professor, Gregory Sholette embodies multiple ways that artists can interrogate history, politics, and public discourse. Through his initial work with the group REPOhistory (1989-2000) (as in, “repossessing history”), he, along with other art groups and individuals of the 80s and early 90s, effectively drew attention to the artist as a social and political actor. Sholette’s collaborations with REPOhistory also presented art works as vehicles for addressing submerged socio-political histories, such as in the group’s Lower Manhattan Sign Project (1992-1993), in which they posted signs around Manhattan offering information about “the unknown or forgotten history of Manhattan below Chambers Street.” Sholette has also been an active participant in PAD/D (Political Art Documentation and Distribution [1980-1986]), an organization devoted to the publication and distribution of documents regarding the intersection of aesthetic politics and activism. Most recently Sholette has founded an archive for futures that “never happened” (The Imaginary Archive, 2010-present), and has been involved with The Institute for Wishful Thinking, an organization that attempts to harness the “untapped” potential of artists by soliciting proposals for projects which might effect governmental and social change.

Despite Sholette’s robust participation with other artists and activists and his tendency to only exhibit his own work in group shows, the works and projects he has produced independently of collaboration feedback vitally into a more collective practice (something he discusses at length below and in a previous “Inside the Artist’s Studio” feature). Meeting Sholette in person, I was struck by his interest in subjects ranging from the popular to the occult and counter-cultural. Sholette’s range of interests are brought to a focus in the book Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, in which he considers artworks that have fallen through the cracks of official art-historical discourse. Such works offer sites of (potential) resistance and autonomy inasmuch as they are not perceived as “art” proper and so remain liminal to the expropriative tendencies of cultural capital. Works by the “outside” artist, the craft artist, the hobbyist, the amateur, and the self-critical “drop-out” appear throughout Sholette’s book, offering examples, if not models, of what art can do guided by different values and habits.

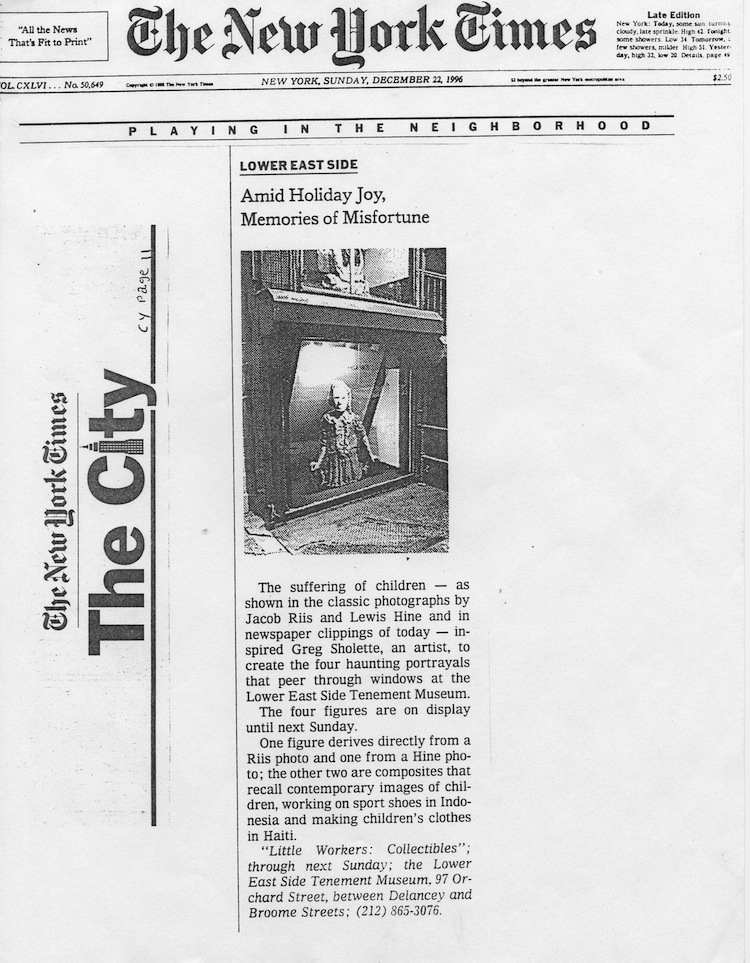

After the work of the film-essayist Chris Marker or the literary theorist Walter Benjamin (two professed heroes of the artist), Sholette turns his attention to the abandoned and unattended, cultural products so prosaic that they would seem neither worthy of our critical attention, nor our powers of reappropriation. The stuff ripe for re-use in Sholette’s work one would hardly call “redemptive,” and yet something is redeemed through the artist’s taking them up—a potential to make legible things just below the attention, what becomes “dark matter” because the culture at large just doesn’t know where to put it. Through the use of action figures in particular, a preferred format of hobbyists, he addresses problems ranging from post-Fordist labor practices (i am NOT my office, 2002-2004) to representations of Italian Fascism (Deconstructing Mussolini, 2007) and the exploitation of child workers (Little Workers Collectibles).

Sholette’s dirty messianic approach also comes across in his appropriation of dioramas, window and museum displays, and souvenirs. Playing upon our familiarity with these 19th century formats, Sholette moves fluidly between sentimentality and criticality, ironic abandon and the recognition that, as Walter Benjamin famously wrote (and Sholette quotes through a particular work of his citing the relationship between John D. Rockefeller’s founding of the New York MoMA and management of his public image after a mining disaster): “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” Moving within the flicker of “civilization” and “barbarism,” Sholette tells history slant, through the eyes of the losers, the unrecognized (and unrecognizeable), citing the places where anomalies and antagonisms crucial to history’s retelling “flash-up.”

Oriented by the Cold War era (as he recognizes below), Sholette’s analysis of barbarism and civilization deconstructs American exceptionalism in the post-war period, particularly the ways that American art and the management of its geopolitical interests intersect. In his video Return of the Atomic Ghosts (2005), for example, Sholette spoofs extraterrestrial cover-up documentaries in order to reveal another cover-up of the previous half-century: the US government’s involvement in countless foreign coups, assassinations, and occupations.